Prof. John Rizvi, Esq.

This Immortal Invention is a Masterclass in Simplicity

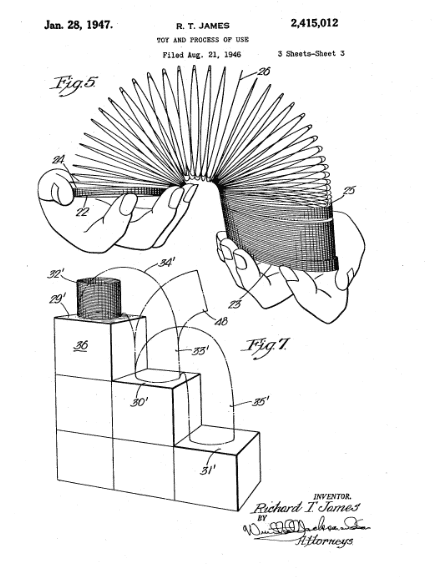

The way it wiggled when it hit the floor struck Richard T. James like a sledgehammer welded by the inventing gods themselves. The torsion spring had fallen off his desk and “stepped its way down” to the floor in a magical spring-like fashion that conjured up the idea for the world-famous Slinky® toy that he successfully patented in 1947. This timeless invention has lessons for the modern-day inventor!

The Creative Spark

After the ravages of World War II, America was ready for some amusement and idle joy and James knew it. While he spent his day job working as a mechanical engineer for the Navy, his restless mind had patiently waited for that creative spark.

As he picked up the clump of springs off the floor, the simplicity and elegance of its accidental slinky motion spurred James into building a prototype toy that would eventually earn over $300 million dollars in commercial revenue.

His wife, Betty James, would later state: “It wiggled, and he thought he could make a toy. I could have seen a whole bunch of springs fall off and not seen it.”

While James had spent years perfecting sensitive cushioning devices for Navy destroyers, the idea of making a toy built upon a single spring consumed his free time. He rushed home to Betty proclaiming, “I can make a toy out of this spring.”

Appetite For Risk

When I look at what James did next, I am reminded of similar inventing journeys taken by other clients of mine including Marguerite Spagnuolo, Valerie Carbone, Alex Gomez, Andy Castellanos, and David Cogswell.

They all shared one overriding attribute: An appetite for risk

In James’s case he ignored the naysayers and comments that “it will never work” and proceeded to borrow $500 to build a machine to manufacture the novelty toy. Today that equates to nearly $8,000 in capital – a large sum for most small, independent inventors in the United States.

Gomez, mentioned above, dropped out of medical school and borrowed money from friends and family to acquire patent protection and build the first prototype.

At some point in your inventing journey you will need to ignore people telling you that you’re crazy to continue down the invention path. Instead, focus on your inner belief in your product. This may involve taking a financial risk or quitting your current job to go the final mile.

A Different Time

Prior to 2013, Inventors like James were required to have a working prototype accompany any patent application. This fell under the First to Invent framework that made life extremely challenging for “Average Joe” small inventors who often worked with limited capital and time to produce a working prototype. Today, inventors have a much smoother path to acquiring patents under the First to File model provided by the United States Patent Office (USPTO).

Smaller Inventors Now Have The Upper Hand

Listen to my recent radio interview

When Bert Martinez, a well-known marketing consultant and media personality recently interviewed me on his Money for Launch Radio Show, he expressed his surprise – as most entrepreneurs do – when I told that one of the biggest patent law modifications in the last 100 years has shifted the tide in favor of small, everyday inventors.

Inventor in Motion

James was convinced he had a commercial hit on his hands and was prepared to risk capital and time on building a prototype that would win patent approval. He spent the next 12 months using the startup funds to perfect a machine that meticulously refined a coil of steel until it produced a pleasing end-over-end motion movement.

The finished prototype included a 2.5 inch sack of 98 coils made out of high carbon steel wire measuring 0.0575 in diameter. It was the perfect example of a tension spring. It would later be studied by physics professors who marveled at its total collapse time of 0.3 seconds corresponding to the amount of time required for a wave front to propagate down the spring to communicate the release of the top end.

Name Sleuth

While he perfected the prototype, Betty proceeded to narrow down potential names for the toy. She spent hours rifling through the dictionary. “I never named a toy in my life, and some of the things that came to mind were awful. Eventually, I looked in the dictionary and I found ‘slinky’ and that was it.” I often remind inventors that naming your product is liking naming a child: It has a deep personal mystical aura that gives your invention wings and motivates you to take the next step.

Sara Blakely, the billionaire inventor of Spanx® describes how at one point she was considering “Open Toed Delilahs” before settling on the more modern and cheeky name we are familiar with today.

Betty James would later state that the Slinky® was like having a seventh child!

Together the couple had fulfilled two key requirements when it comes to launching a new invention and receiving patent protection from the USPTO: It was unique and technically feasible. There was nothing on the American toy landscape that rivaled the hypnotic movement and simplicity of the Slinky®.

Will The Slinky® Sell?

But, a third question remained if Betty and James were to ultimately acquire a utility patent: Was it really commercially viable?

The industrious pair set out to prove this for themselves by manufacturing a small inventory of Slinky® toys. They approached several companies before Gimbels department store in Philadelphia agreed to sell 400 of them over the Christmas holiday season.

“They gave us the end of a counter to sell the Slinky®,” recalls Betty. Unfortunately, sales were slow to non-existent during the first several days.

They faced the same challenges as the inventors of the Post-It Note® and Grandmas2Share® in their commercial infancy: Getting the public to understand and embrace their product. It’s an unfortunate fact that a simple spring among electric trains and other highly appealing Christmas toys made their invention virtually invisible to shoppers.

The Genius Move

When he learned of the problem, James went down to the department store himself. After setting up a more eye-catching display, he gave dynamic interactive demonstrations, selling 400 units within 90 minutes. By Christmas, his $1 product had sold out – nearly 20,000 in total!

Both kids and parents went crazy over a product “not burdened with complex ideas” as one book author put it. “It doesn’t require anyone else to be in the room with the kid and the toy. And, apart from the spinoffs, it doesn’t have an imposed personality.”

Today its estimated that over 350 million people have purchased the Slinky® toy, an amazing accomplishment for an inventor who stumbled upon the idea purely by accident!

Patent Pending

By the time he filed his utility patent the USPTO had irrefutable proof that the Slinky was novel, unique and commercially viable. The Slinky® was successfully patented around 1947 – two years after end of World War II. It has a timeless mechanical quality much like the later invention of the Rubik’s Cube®. Both toys are inherently “evergreen” when it comes to long-term commercial value.

The Next Generation

In fact, both toys have found new converts in recent years. Movies like Toy Story have featured the Slinky® while the gaming community has embraced speed-solving activities around the Rubik’s Cube®.

In my recent TED Talks and guest appearances on CBS and NBC news segments I stress to micro-entrepreneurs that you do NOT need a build a flux capacitor to acquire a patent or achieve commercial success. The Slinky®, Rubik’s Cube® – along with other simple inventions like EyeBandz® and Toilet Purifier® – show us the value of tiny, innocuous ideas that capture the heart of a nation.

A New Leader Emerges

While James was the genius behind conceiving and building the Slinky®, it would be his wife Betty who would guide the newly established company, James Industries, through the tumultuous decades ahead, including the topsy-turvy days of the 1960s. She was also forced along this path when her husband James decided to leave her (and the Slinky®) and join a religious cult in Bolivia. In a male dominated industry, she developed a sound business acumen that helped make the Slinky® one of America’s favorite toys of all time.

One of Betty’s sagest business moves was to put the Slinky® on Television. She created a jingle to accompany the product which is considered one of the most popular advertising jingles in history.

Today the Slinky® toy has a 90% recognition rate in the United States. It continues to be manufactured on our shores and sells for around $3. It’s considered an American icon in the pantheon of inventions passed down from one generation to the next.

Question Mark

While America continues to have an unbreakable love affair with the Slinky®, kids do have one question they wish they could ask the original inventors:

Why can’t you make a Slinky that does not twist or break?

I like to remind our younger generation that every great invention arguably needs to have one TINY flaw to remind us of the human qualities imbued into the product including love, fear, perseverance, sweat, toil, and of course, failure.

No inventor is perfect and perhaps the same can be said of his invention.